Rotator Cuff Tears and Treatment Options

Rotator cuff tears are a common source of shoulder pain. The incidence of rotator cuff damage increases with age and is most frequently caused by degeneration of the tendon, rather than injury from sports or trauma. Although the information that follows can be used as a guide for all types of rotator cuff tears, it is intended specifically for patients with complete degenerative tears of the rotator cuff. Treatment recommendations vary from rehabilitation to surgical repair of the torn tendon(s). The best method of treatment is different for every patient. The decision on how to treat rotator cuff tears is based on the patient's severity of symptoms, functional requirements, and presence of other illnesses that may complicate treatment. In consultation with an orthopaedic surgeon, the information that follows is intended to assist patients in deciding on the best management of their rotator cuff tear with the understanding that all patients are unique. |

Anatomy and Pathophysiology

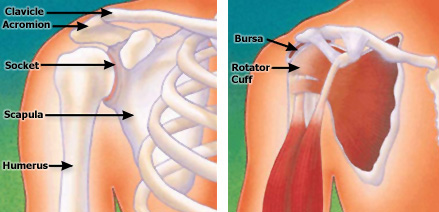

The rotator cuff is a group of four muscles that surround the humeral head (ball of the shoulder joint). The muscles are referred to as the "SITS" muscles: supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, and subcapularis. The muscles function to provide rotation, elevate the arm, and give stability to the shoulder joint (glenohumeral joint). The supraspinatus is most frequently involved in degenerative tears of the rotator cuff. More than one tendon can be involved. There is a bursa (sac) between the rotator cuff and acromion that allows the muscles to glide freely when moving. When rotator cuff tendons are injured or damaged, this bursa often becomes inflamed and painful.

Pain, loss of motion, and weakness may occur when one of the rotator cuff tendons tears. The tendons generally tear off at their insertion (attachment) onto the humeral head.

Incidence

Rotator Cuff Tears (http://www.orthoinfo.org/topic.cfm?topic=A00064) increase in frequency with age, are more common in the dominant arm, and can be present in the opposite shoulder even if there is no pain. 1, 7 The true incidence of rotator cuff tears in the general population is difficult to determine because 5% to 40% of people without shoulder pain may have a torn rotator cuff. This was determined by studies using X-rays, CT Scans and MRIs (http://www.orthoinfo.org/topic.cfm?topic=A00188) to assess the shoulders of patients with no symptoms. One study revealed a 34% overall incidence of rotator cuff tears. 6 The highest incidence occurred in patients who were older than 60 years. This study supported the concept that rotator cuff damage has a degenerative component and that a tear of the rotator cuff is compatible with a painless, normal functioning shoulder.

Etiology

There are intrinsic and extrinsic factors that cause rotator cuff tears. An example of an intrinsic factor is tendon blood supply. The blood supply to the rotator cuff diminishes with age and transiently with certain motions and activities. The diminished blood supply may contribute to tendon degeneration and complete tearing. 3, 4, 5 The substance of the tendon itself degenerates over time. Because of an age-related decrease in tendon blood supply, the body's ability to repair tendon damage is decreased with age; this can ultimately lead to a full-thickness tear of the rotator cuff.

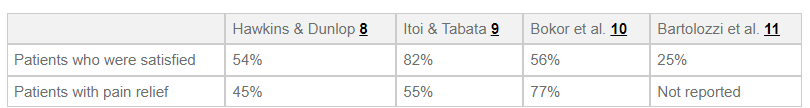

An extrinsic factor that can cause damage to the rotator cuff is the presence of bones spurs underneath the acromion. The spurs rub on the tendon when the arm is elevated; this is often referred to as Shoulder Impingement (http://www.orthoinfo.org/topic.cfm?topic=A00032) Bone spurs are another result of the aging process. The rubbing of the tendon on the bone spur can lead to attrition (weakening) of the tendon. Combining this with a diminished blood supply, the tendons have a limited ability to heal themselves. These factors are at least partly responsible for the age-related increase in rotator cuff disease and the higher frequency in the dominant arm.

During surgery to repair a torn rotator cuff in this instance, the spur is typically removed to relieve the impingement. Removing the spur is referred to as an "acromioplasty".

Natural History

What will happen if a torn rotator cuff is not treated with surgery? Will I lose the use of my arm? Will the tear get larger over time? These are common concerns patients have, and the answers are not always clear. In one study, 40% of patients with a rotator cuff tear showed enlargement of the tear over a 5-year period; however, 20% of those patients had no symptoms. Therefore, less than half of patients with a rotator cuff tear will have tear enlargement, but 80% of patients whose tear enlarges will develop symptoms. 7 These data, however, are based on a small group of patients; it is important to realize that once symptoms develop, progression may have already progressed and enlarged.

Surgical and Nonsurgical Options

Treatment options include:

- Nonsurgical (conservative) treatment

- Surgical treatment (rotator cuff repair)

- Open repair

- Mini-open repair

- All-arthroscopic repair

Nonsurgical Treatment: Benefits and Limits

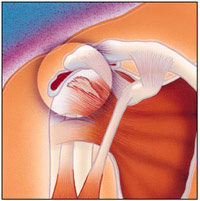

Nonsurgical treatment typically involves activity modification (avoidance of activities that cause symptoms). Nonsurgical management of a rotator cuff tear can provide relief in approximately 50% of patients.

These studies show that approximately 50% of patients have decreased pain and improved motion and are satisfied with the outcome of nonsurgical treatment. Surgeons may recommend nonsurgical treatment for patients who are most bothered by pain, rather than weakness, because strength does not tend to improve without surgery.

There are a few predictors of poor outcome from nonsurgical treatment:

- Long duration of symptoms (more than 6 to 12 months)

- Large tears (more than 3 centimeters)

Nonsurgical treatment has both advantages and disadvantages.

Surgical Intervention and Considerations

Surgical management is indicated for a rotator cuff tear that does not respond to nonsurgical management and is associated with weakness, loss of function, and limited motion. Because there is no evidence of better results in early versus delayed repairs, many surgeons consider a trial of nonsurgical management to be appropriate. 1 Tears that are associated with profound weakness, are caused by acute trauma, and/or are very large (greater than 3 centimeters) on initial evaluation may also be considered for early surgical repair. Surgical treatment of a torn rotator is designed to repair the tendon back to the humeral head (ball of the shoulder joint) from where it is torn. This can be accomplished in a number of ways. Each of the methods available has its own advantages and disadvantages; all have the same goal—getting the tendon to heal to the bone. The choice of surgical technique depends on several factors, including the surgeon's experience and familiarity with a particular procedure, the size of the tear, the patient's anatomy, the quality of the tendon tissue and bone, and the patient's needs. Regardless of the repair method used, studies show similar levels of pain relief, strength improvement, and patient satisfaction.

The three commonly used surgical techniques for rotator cuff repair are:

- Open repair

- Mini-open repair

- All-arthroscopic repair

An individual surgeon's ability to repair a torn rotator cuff and achieve a satisfactory result varies by technique. Variation is based on experience and familiarity with the technique. Although one surgeon may be capable of achieving a quality repair through all-arthroscopic means, another may have better results with mini-open repair. Prior to surgery, patients should discuss the options available to them with their surgeon. The surgeon can share results of using different techniques so that the most appropriate treatment plan can be designed.

Advantages:

- Patient avoids surgery and its inherent risks:

- Infection

- Permanent stiffness

- Anesthesia complications

- Patient has no "down time"

Disadvantages:

- Strength does not improve

- Tears may increase in size over time

- Patient may need to decrease activity level

Surgical Procedure

Open Repair

Open repair is performed without arthroscopy. The surgeon makes an incision over the shoulder and detaches the deltoid muscle to gain access to and improve visualization of the torn rotator cuff. The surgeon will usually perform an acromioplasty (removal of bone spurs from the undersurface of the acromion) as well. The incision is typically several centimeters long. Open repair was the first technique used to repair a torn rotator cuff; over the years, the introduction of new technology and improved surgeon experience has led to the development of less invasive surgical procedures. Although a less invasive procedure may be attractive to many patients, open repair does restore function, reduce pain, and is durable in terms of long-term relief of symptoms. 12, 13

Mini-Open Repair

As the name implies, mini-open repair is a smaller version of the open technique. The incision is typically 3 cm to 5 cm in length. This technique also incorporates arthroscopy to visualize the tear and assess and treat damage to other structures within the joint (it is used to asses the Shoulder Surgery Exercise Guide (http://www.orthoinfo.org/topic.cfm?topic=A00067) and remove the spurs under the acromion). Arthroscopic removal of spurs (acromioplasty) avoids the need to detach the deltoid muscle. Once the arthroscopic portion of the procedure is completed, the surgeon proceeds to the mini-open incision to repair the rotator cuff. Mini-open repair can be performed on an outpatient basis. Currently, this is one of the most commonly used methods of treating a torn rotator cuff; results have been equal to those for open repair. The mini-open repair has also proven to be durable over the long-term. 14

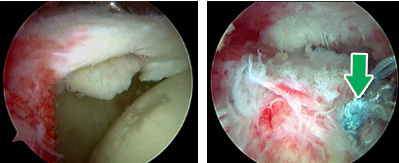

All-Arthroscopic Repair

This technique uses multiple small incisions (portals) and arthroscopic technology to visualize and repair the rotator cuff. All-arthroscopic repair is usually an outpatient procedure. The technique is very challenging, and the learning curve for surgeons is steep. It appears that the results are comparable to those for mini-open repair and open repair. 15

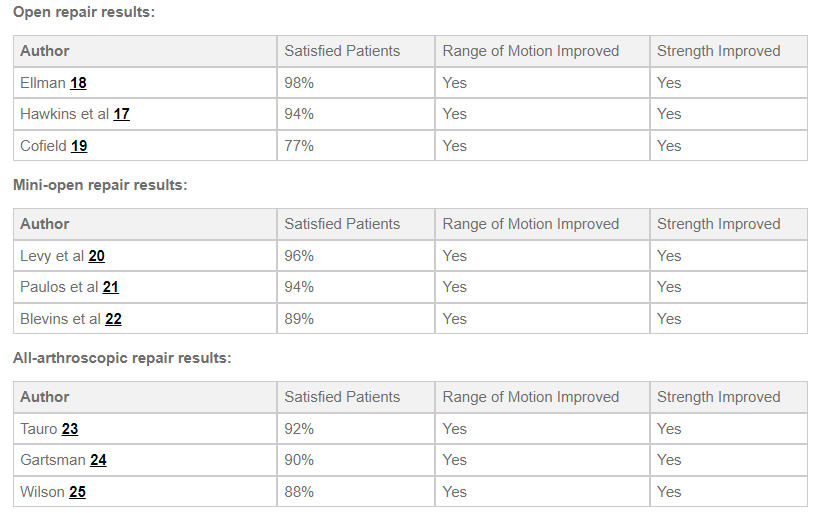

Results

After rotator cuff repair, 80% to 95% of patients achieve a satisfactory result, defined as adequate pain relief, restoration or improvement of function, improvement in range of motion, and patient satisfaction with the procedure. Certain factors decrease the likelihood of a satisfactory result: 16

- Poor tissue quality

- Large or massive tears

- Poor compliance with postoperative rehabilitation and restrictions

- Patient age (older than 65 years)

- Workers' compensation claims

Surgical techniques for rotator cuff repair have progressed to more minimally invasive procedures. With each advance in technique, surgeons experience a learning curve to master the new technique. Initially, some tears were considered too large to be treated with less invasive techniques. As surgeons become more experienced in using less invasive techniques, they are better able to treat most tears with less invasive means. The most recent development is the all-arthroscopic technique.

Each step toward less invasive surgery has benefited the patient by:

- Decreasing pain from surgery

- Decreasing postoperative stiffness

- Decreasing surgical blood loss

- Decreasing length of stay in the hospital

Each technique has similar results in terms of satisfactory relief of pain, improvement in function, and patient satisfaction. Less invasive surgery results in an easier rehabilitation process and less postoperative pain.

The above studies represent only a few of many articles on this topic. A large review of all published material relating to outcomes from rotator cuff repair surgery was presented in 2003. 30 This article demonstrated that:

- Results were equal for open, mini-open, and arthroscopic repair techniques when comparing:

- Patient satisfaction

- Pain relief

- Strength

- Surgeon expertise is more important in achieving satisfactory results than the choice of technique

Improvement in pain, function, and strength typically occurs over a 4 to 6 month period following the procedure.

This is a non-exhaustive list of potential additional resources. AAOS does not review or endorse accuracy or effectiveness of materials, treatments or physicians.

Complications

The overall complication rate following rotator cuff repair surgery is estimated to be approximately 10%. This is based on a large review of 40 published series on rotator cuff repairs. 26 Complications generally involve:

- Nerve Injury (1% to 2%): Nerve injury usually involves the axillary nerve, which activates the deltoid muscle. Careful surgical dissection and limiting forceful manipulation and traction on the arm during surgery will decrease the likelihood of nerve injury.

- Infection (1%): Use of antibiotics during the procedure and sterile surgical technique limits the risk of infection. Antibiotic use after discharge from the hospital does not further decrease risk of infection.

- Deltoid Detachment (less than 1%): Careful repair of the deltoid and protection during rehabilitation after an open repair procedure are important to avoid deltoid detachment. This complication should not occur after a mini-open or arthroscopic repair because these procedures preserve the deltoid attachment or do not require detaching the deltoid.

- Stiffness (less than 1%): Early rehabilitation protocols decrease the likelihood of permanent stiffness or loss of motion following a rotator cuff repair.

- Tendon Re-tear (6%): Several studies have documented tearing of the rotator cuff following all types of repairs. It appears that tendon re-tear does not guarantee a poor result, return of pain, or poor function. 27, 28 A recent study comparing rates of tendon re-tear showed a higher rate of tendon re-tear with all-arthroscopic repair when the tear was more than 3 cm. Smaller tears had a similar rate of re-tearing when comparing open and arthroscopic repairs. Again, there was little difference in patients' function regardless of whether there was tendon re-tear.

Rehabilitation/Convalescence

Following rotator cuff surgery, therapy progresses in stages. Initially, the repair needs to be protected until adequate healing of the tendon to bone occurs. For this reason, most patients use a sling for the first 4 to 6 weeks after surgery and are instructed to limit active use of the arm during this period. Passive range-of-motion exercises are begun with a therapist; () may be taught as well. Progressive strengthening and range-of-motion exercises continue during the next 6 to 12 weeks. Most patients have a functional range of motion and adequate strength by 4 to 6 months after surgery.

Summary

The incidence of full-thickness rotator cuff tears increases with age; however, tears are not always painful. Tears can be managed successfully with nonsurgical treatment in 50% of patients. Pain and range of motion will improve with nonsurgical management, but strength will not. Large tears, significant weakness, and an acute traumatic event are possible causes of poor outcome from nonsurgical management.

Surgical repair results in pain reduction and improved function and strength in more than 80% of patients. About one in ten surgeries can result in complications. Surgical procedures to repair a torn rotator cuff have become increasingly less invasive. Minimally invasive procedures are less painful and have less blood loss, shorter hospital stays, and a generally easier rehabilitation period. Although less invasive procedures are more attractive, they are often more difficult for the surgeon to perform and require an experienced surgeon for best results. Lastly, all repair methods appear equal in outcomes when the surgery is performed well.